Introduction

The term ‘mentoring’ is used in many different contexts, but in order to establish a definition in the context of teacher education, we may say that ‘mentoring is typically described as a process to help develop teaching practices, involving a nurturing relationship between a less experienced and a more experienced person, who provides guidance as a role model and adviser.’ (Bigelow, 2002; Haney 1997). This definition would seem to encapsulate the essence of mentoring in teacher education and is readily applicable to the context of this research study. The mentor-mentee relationship is by definition reciprocal and collaborative in that, while the mentor provides support, feedback and information, as well as modelling appropriate practice to the mentee, the latter, in turn, engages in a dialogic process by maintaining a flow of information to the mentor in terms of their professional and personal development and concerns as they embark on their initial or early teaching career. As such, the mentor-mentee relationship can be likened to a ‘master-apprentice’ relationship – although it should be mentioned that the mentee can provide an impetus for the mentor to also develop as a more rounded professional. For example, mentoring can be seen as an essential tool of continued professional development (CPD), as the mentor might well be motivated in their role to expand their perspectives within the profession away from the bread-and-butter work of teaching in the classroom.

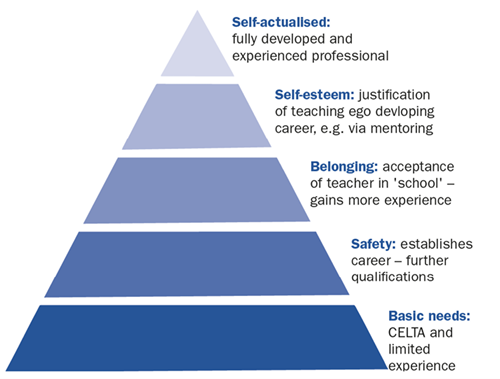

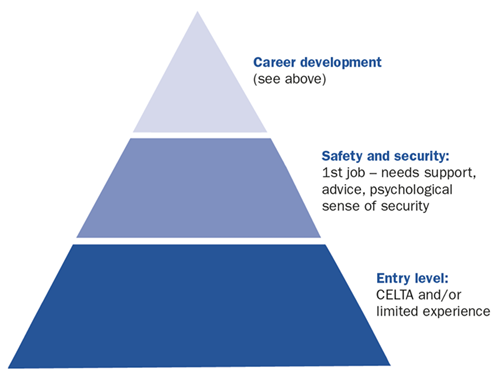

The mentoring paradigm might be seen as analogous to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. In order to conceptualise this, we can look at three hierarchies, including Maslow’s original hierarchy (Figures 1–3).

It can be observed that as far as the mentoring process is concerned, it is the second stage towards the base of the pyramid which is vitally important for the mentee. Having gained initial qualification through the CELTA or an equivalent, the mentee then pursues their career as a TEFL teacher. Crucially, however, the success or otherwise of this initial teaching experience is dependent upon the second stage (safety and security). This is true not only for the mentee, but also the other stakeholders in the institution such as: students; directors of studies; senior teachers; school directors; and others. If successfully negotiated, all stakeholders stand to benefit but, for our purposes, most essentially the ‘new’ teacher benefits. This is the point at where the mentor comes to prominence. The mentee’s need for support, advice and a psychological sense of security can potentially be met by the mentor. Regarding the mentor, they are likely to be motivated in the role of mentor by a desire to achieve a higher position on the teacher’s hierarchy of needs – to the stages of ‘self-esteem’ and ‘self-actualisation’. At these stages the mentor has acquired extensive experience in the classroom and has probably furthered their qualifications – for instance, through the DELTA and/or a postgraduate degree. Assuming that the mentor is motivated to develop further, it is plausible that they will adopt an approach in which the sharing of acquired knowledge will appeal, as it will help to justify their raison d’etre in the profession.

The research

Background and mentee

The research was carried out at the British Council in Warsaw, Poland, and featured teachers at an early stage of their teaching careers. The British Council in Poland utilises a foundation entry system in which newly qualified teachers or teachers with limited experience can join the organisation on the proviso that they commit to a professional development programme. This programme comprises an induction programme, an in-house teaching course named the ‘Teaching Support Programme’ (TSP), and a mentoring system which aims to support and integrate these new teachers into the teaching style of the British Council. Within Poland (the British Council has teaching centres in Warsaw, Krakow and Wroclaw) there are five foundation entry teachers this academic year. Mentoring is seen as an essential part of the foundation programme. One of the mentees is Dutch and has completed his master’s studies in the Netherlands. The second mentee is British born and has recently completed his CELTA. He started working at the British Council in January of this year. The other mentees are L2 English speaker teachers, two from Poland and one from Ukraine. Two of these teachers worked as learning assistants at the British Council before becoming teachers. They have all completed master’s studies and most have completed the CELTA. These teachers work with a variety of age groups and levels, but most are either primary (5–11-year-olds) or secondary (12–17-year-olds) teachers.

As a mentor at the British Council in Warsaw, over the last few years, I have been interested in analysing how effective the mentoring has been. Anecdotal evidence suggested that for the mentees, mentoring was indeed effective, but I wanted to gain a deeper insight into how the mentoring process impacted on the mentees and so I decided to carry out a survey and interview my mentees.

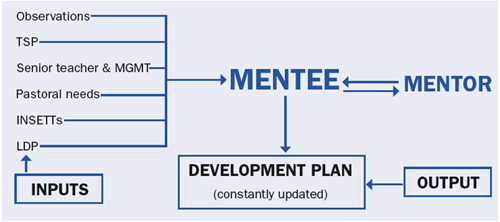

Developing an improvement plan (see Appendix 2 Resources online)

A foundation entry level teacher will typically be observed very early on in the academic year and a mentor – appointed by the teaching centre management (MGMT) – is made fully aware of the feedback the teacher received. Based on feedback from the original observer, the mentor then arranges an initial meeting with the mentee and a development plan is drawn up. While feedback from the initial observation is obviously important, it is not the only determinant of the plan. During the initial discussion, other perceived areas for development are also integrated into the plan. It should be emphasised that the development plan is a dynamic document and changes as perceived needs emerge. For instance, subsequent observations might uncover other developmental needs or other needs might emerge in discussions between the mentor and mentee, which need addressing. The development plan is therefore a ‘live’ document which is subject to the emerging needs of the mentee.

Parallel to the mentoring plan, the mentee also follows a teaching support programme (TSP) in which they follow a British Council course covering the basic areas of effective classroom teaching (lesson planning, classroom management, etc.). The mentee is observed several times during the academic year with the observation focused on each of these basic areas. The observation is either carried out by the mentor or, alternatively, an academic manager; the feedback from these observations contributes to updating the mentee’s development plan.

Aside from the ‘academic’ aspects of the plan, pastoral care is also part of the development plan. For instance, it might be that a personal issue is having a negative effect on classroom performance, so the mentor encourages a relationship in which the mentee can feel comfortable discussing personal issues – perhaps, for example, the mentee is having some settling-in problems in what is likely to be a new environment.

Implementing the plan

As mentioned above, the plan for the mentee derives from a combination of areas which have been flagged for development from: their observation feedback; the TSP programme; the learning and development plan; and from discussion and consultations between the mentee and the mentor. The plan is then implemented over the academic year and discussed weekly with the mentee to check progress. The plan is dynamic and further areas for development are added and implemented accordingly. Additionally, personal and pastoral care is included in the plan so a more holistic approach is provided for. Weekly meetings between mentor and mentee give each party an opportunity to update the other regarding the effective implementation of the plan.

In implementing the plan, the mentor is in contact with a senior teacher and sends the latter a weekly update of the meeting with the mentor. The senior teacher will also update the mentor with details of any observations or other developments regarding the mentee.

Observing the effects of the Plan

From all perspectives – mentee, mentor, senior teachers, management and, ultimately, students – it seems the mentoring plan worked well and yielded mutual benefits for all concerned.

The mentee is the greatest beneficiary because they are placed at the centre of the plan. Without a mentoring process the mentee might well find integration into the organisation jarring and challenging. The mentoring plan is in place to help the new teacher manage this integration. Evidence from the survey and anecdotal feedback suggests that the mentoring process and development plan do help the mentee settle into their new working environment (see below). As regards the mentor, the plan enables the mentor to organise the process of the teacher’s integration into a new working environment in an efficient way. The holistic layout of the plan means that potential problems and issues can be anticipated and accommodated into the plan. Thus, the mentor has a tool which is instrumental in smoothing the process and establishing meaningful criteria for the successful integration of the teacher. The organisation (in this instance, the British Council) needs to ensure that newly recruited teachers settle in as smoothly and quickly as possible, so they (the teachers) are ready to execute teaching duties to as high a standard as possible.

Reflection on the effects of the plan

The survey was carried out on MS Forms (see Resources online at www.modernenglishteacher.com/media

/43511/met_341_online_resources_appendix1and2_richardcowen.pdf). In total, I asked 13 open questions, aiming for more qualitative rather than quantitative feedback. As there were relatively few mentees in this case study, I thought this was a good opportunity to undertake deeper research through a qualitative approach. I then interviewed the mentees to further substantiate their responses from the survey to gain greater insight into their responses.

The findings of the survey were overwhelmingly positive. Virtually all the teachers had a first degree and had completed the CELTA before commencing work at the British Council.

Expectations of mentoring (Q2) included: ‘someone experienced in the field who would be prepared to help a less experienced teacher’ to ‘someone to help me create interesting lessons’ and ‘someone who will guide and advise me whenever required’.

The reality of being mentored (Q3) included one comment in which the mentoring ‘was not as intimidating as expected’ to ‘just as expected’. One mentee added: ‘there was lots of emotional and mental support, so I felt comfortable about being myself’.

For Q5, mentees found that expectations had been met, even exceeded. For Q6, mentees found that the practical help and advice given ‘was irreplaceable’ and that ‘I had a terrific rapport with my mentor’. Likewise, for Q7, mentees unanimously commented that mentoring had had a positive impact on their teaching, especially for those mentees who were faced with teaching either YL or early years. Help and advice with classroom management issues were to the fore here. Regarding Q10, again, all the mentees agreed that the mentoring process had helped them feel more settled in their relatively new environment. Q11, improvements to the mentoring process, included a request for ‘group mentoring sessions’ to work alongside individual mentoring – something which we will consider in next year’s mentoring programme. Another request was that perhaps it would be an idea to having a ‘meet the mentor’ session at the beginning of the year to help lessen stress before initially meeting their personal mentor. For Q13, one teacher compared the ‘new teacher’ experience of a colleague at another school who did not receive any mentoring and was directly thrust into the classroom. She commented that she could not imagine such a situation compared with the mentoring process at the British Council.

Conclusions

It is quite clear that the mentoring process at the British Council has been very successful and that all stakeholders have recognised the positive impact and consequent benefits which have accrued due to the process. At the centre of the process is, of course, the mentee. They are at the beginning of the academic year, faced with having to quickly integrate into the teaching centre. They are expected to cope with myriad challenges which, in turn, can be intimidating, especially at a school with high expectations of teaching excellence. The mentoring process seeks to assist the new teacher in overcoming the physical and mental obstacles the teacher will face this daunting new environment. The mentor is charged with providing a cushion for the mentee – helping to absorb pressure and smooth the new teaching environment the teacher finds themself facing.

As a consequence, it is very clear that new, inexperienced teachers will benefit enormously from the establishment of a mentoring system and process. The mentoring process acts as a ‘buffer’ in that the mentee feels protected and more secure while at the same time the system provides for a ‘transition’ stage allowing the new teacher to settle into their environment, knowing that they have the support of an experienced person to fall back on and seek advice from, as and when required. From the point of view of the mentor, the process enables the seasoned teaching professional to pass on their experience and know-how to the new teacher. As such, mentoring at its best enacts a community of practice (COP) where the expert, experienced practitioner helps and supports the apprentice teacher as they embark on the early stages of their teaching career. Speaking from personal experience, the mentor is giving back something to the profession as they pass on advice and a measure of expertise from their teaching career and experience.

My research has substantiated and confirmed my initial thoughts that mentoring is an essential tool in facilitating the integration of new teachers into the school. One might turn to Krashen’s affective filter hypothesis and apply this equally well to the new teacher as to students. It seems highly likely that the new teacher’s classroom experience is more likely to be positive and effective if they feel secure and comfortable in their role, knowing they have someone reliable and trustworthy to turn to if and when difficulties occur in and out of the classroom. I would therefore highly recommend that schools establish a mentoring programme to ensure new teachers are able to integrate as smoothly as possible into the school and fulfil the demands placed upon them by students, senior teachers, and school management.