A prudent question is one half of wisdom.

– Francis Bacon (philosopher) 1561–1626

Invariably, when I invite my students to ask me questions to get to know me (better), especially on the first day of class to create the right atmosphere and to establish a conducive teaching-learning environment, a familiar pattern of questions emerges. I also realised that this happens regardless of whether the questions come spontaneously from individuals around the classroom in an open-floor format or in written form (anonymously) on paper in small, structured groupwork after a process of interaction.

Common questions asked of me tend to be of the closed type that require either a simple yes or no answer or a very short factual response. For example:

What is your nickname?

Do you like Japanese pop music?

Can you eat natto? (Japanese fermented soy beans that have a pungent aroma)

What season do you like?

Are you from America / UK / Canada / Australia?

The questions are well intentioned and certainly have value – naturally, I am happy that students are expressing an interest in who I am and are using their language skills to produce questions. However, if we take a closer look at these questions, we notice that they are in fact unrelated to each other, have little value, and are limited in scope because the answers I provide can serve no real purpose beyond the confines of the questions. This means the potential dialogue and conversational flow is halted and even abruptly ended without the sharing of any of my life stories or interesting anecdotes that could pique their interest further and stimulate further questions. Obviously, I could offer more information – self-disclosure operates differently across cultures so some educators may be hesitant about being forthcoming with personal information – but I make it a point to elaborate whenever possible to model the concept of ‘keeping the conversation going’.

While the word ‘what’ can be used to create open questions such as: ‘what do you think about …?’ the inherent nature of questions such as ‘do you / can you / are you?’ remain closed (Figure 1) and do not in themselves necessitate any additional information on my part.

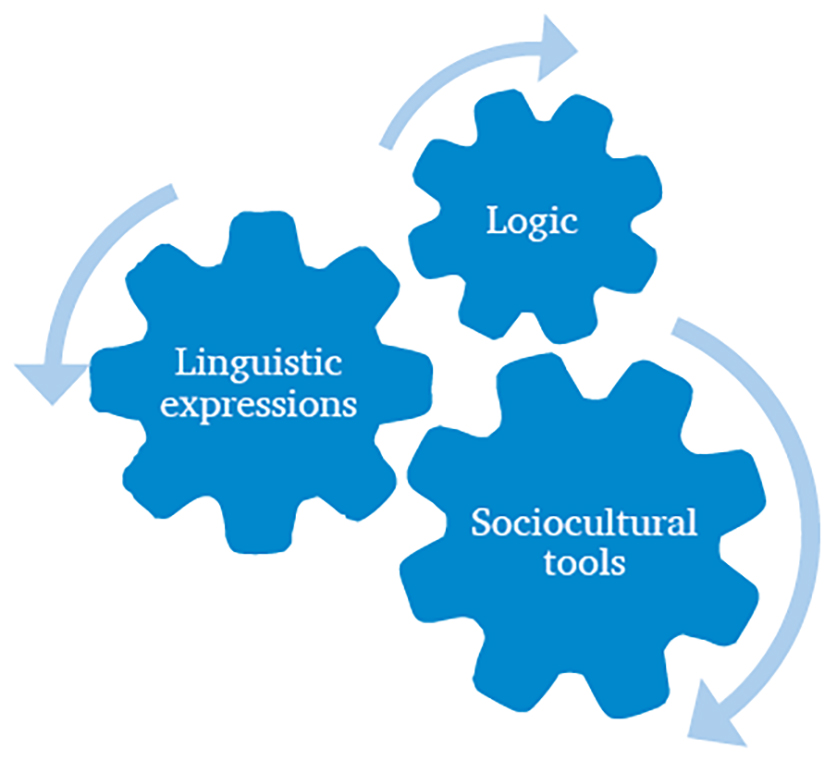

Historically speaking, philosophers and educators have struggled with the curiously thought-provoking question ‘what is a question?’ and similarly wrestled with the tantalisingly head-scratching follow up: ‘what does a question do?’. In essence, the highly theoretical narrative has been guided and shaped by the notions (Figure 2) that ‘questions’ are intrinsically:

- propositions connected to logic that operate in the cognitive domain of reasoning;

- linguistic expressions stemming from the relationship between language and thought;

- sociocultural tools designed to engage others, to elicit a response and develop rapport.

Given the above definitions, the nature and function of questions can be, therefore, characterised and visualised as multipurpose interlocking cogs in a mechanism (Figure 3) that allow us to reflect, express and create our internal and external worlds.

In practical terms, constructing and employing questions, therefore, offers us the opportunity to:

- be curious

- discover something

- interact with others

- forge (lasting) bonds

- establish trust

- acknowledge the existence of others

- show others that we care

- express our commonalities and dissimilarities

- show others that we are attentive and interested

- discover things about ourselves and express them

- inspire, persuade and threaten

- exchange and share ideas, beliefs, values and cultural patterns.

As educators, we intuitively understand the pedagogical need to motivate learners to ask questions – communication being the ultimate goal. In this regard, much has been written in educational research about the importance of fostering wh– questions (who / what / where / when / why / how) as an indispensable vehicle that produces language and generates the need to ask follow-up questions to make communication more successful. In the past, educators have perhaps tended to concentrate more on the exclusive use of factual questions which have the explicit function of testing whether or not learners have retained certain information – questions which are now arguably regarded in a negative light as static, classroom display questions. However, these questions have been largely replaced by the idea of accentuating higher-order questions (Nunan, 1991) which provide optimal conditions for learners to reflect critically on their own:

- knowledge base;

- attitudes;

- beliefs;

- cultural norms; and

- reasoning skills.

Nunan also argues that higher-order questions are further reaching in scope and holistic in nature. In ELT, these higher-order questions are represented as either open or open-ended questions. The title of this article is perhaps a good example of what an open question looks like as it welcomes an explanation or discussion of some kind. In the field of interpersonal communication, researchers overwhelmingly agree that such open questions are hugely impactful and have a ‘transformative power’ because they enable us to gain valuable insight into people’s thoughts, feelings and behaviours – functioning as a set of linguistic tools that give us access to knowledge, problem solving skills and world building by allowing us to make connections between people (O’Hair et al., 2015). Other researchers such as Trenholm and Jensen (2004) emphasise that the implementation of open questions allows us to think more critically and hone perception, and so leads to a better understanding of a situation allowing us to make more informed decisions. As a result, a meaningful dialogue between ourselves and others can be achieved. In comparison to closed questions that limit answers to specific choices, open questions allow for greater freedom in how to respond (Figure 4).

Research in interpersonal communication provides a model of questions that can be beneficial to our understanding of how questions work (Figure 5).

- Funnel (starting with general, broad, open-ended questions at the top and narrower leading to more specific, closed questions at the bottom)

- Inverted funnel (starting with specific, narrow, closed questions at the top leading to more general, open-ended questions at the bottom)

- Tunnel (all the questions are similar in structure – all general or specific)

Given that closed questions in themselves offer fewer possibilities for interaction, should they be avoided? Perhaps not entirely. Such questions do have their rightful place in the classroom, especially when educators require a particular answer to be given (to test a particular language item) and if time pressed. Open questions, on the other hand, evidently help learners to engage at a much deeper level and generate dialogue. However, one type of question perhaps best to avoid (unless learners have an advanced level of proficiency in the target language) is the double-barreled question which includes several questions embedded in one. This can be very confusing and lead to communication breakdown.

When my students are tasked with interviewing foreign tourists in Hiroshima’s Peace Memorial Park for a survey about peace, I always remind them to craft their questions appropriately and mindfully so as to avoid invading the visitors with salvos of personal, unconnected questions that can make the people feel as though they are being interrogated (not peaceful at all). An understanding of these pitfalls can offer students an insight into how culture and communication interlock and how complex interaction across cultures can be. As a guideline, using tips and advice from Trenholm (1995) and Samovar et al. (2017), I discuss with my students in what ways questions can be drafted and reformulated to be:

- culturally appropriate;

- answerable;

- unambiguous;

- nonthreatening; and

- non-leading (the avoidance of directing interviewees to a desired answer).

Given our various teaching-leaning contexts, how can educators encourage learners to ask better questions? One activity I often use is divided into two steps that can be combined or used separately and I would like to share it with MET readers here (Figure 6). Feel free to adapt it to meet the needs of your learners.

These are the two steps:

Step 1: Three things on paper

Step 2: Self-interviews

| Step 1: Three things on paper |

|---|

| In the first step, making sure that everyone has some paper (or card) to write on, ask them to write three things about themselves. These could be one-word items or sentences. |

| When everyone has finished writing, I ask everyone to stand up, walk around the classroom and find a partner (groups of three work well too). They then exchange slips of paper. Next, learners read the statements on their partner’s paper and find out the details using wh questions. Emphasise that behind every statement there is a life story to be explored. |

| After a given period of time, ask everyone to return the sheet of paper, walk around the classroom and find a new partner. This step can be repeated several times allowing everyone to rehearse and rework their responses. |

| Step 2: Self-interviews |

| In the next step, ask everyone to flip over the sheet of paper. Then, ask everyone to think about the three things they wrote about themselves previously and ask them to turn the statements into questions. |

| If anyone is having trouble doing this, I model the following questions on the board: What kind of Italian food do you like cooking? Where do you usually walk? What kind of music do you enjoy listening to? |

| When everyone has finished writing, as before, I ask everyone to stand up, walk around the classroom and find a partner. They then exchange slips of paper. Learners then read the questions on their partner’s paper and ask them in turn. As before, after a given time, everyone returns the sheet of paper, walks around the classroom and finds a new partner. |

| This step can be repeated several times allowing everyone to rehearse and rework their responses. As the questions have already been formulated by themselves, the task is nonthreatening and learners can freely talk on their topics of choice |

The activity can easily accommodate the funnel, inverted funnel and tunnel models of asking questions discussed earlier and encourages:

- the formulation of questions and follow-up questions;

- the practice of asking wh– questions;

- active engagement between learners;

- the rehearsal of responses and opportunities to fine-tune them; and

- the establishment of a safe, nonthreatening space to improve question-making and providing more appropriate and detailed responses.

Negotiating the topic of generating questions in the classroom can be a tricky, challenging yet rewarding aspect of the job of an educator. It is worth mentioning, too, that learners in some cultures are more forthcoming when it comes to asking questions while others follow cultural norms that place greater value on silence, time for quiet reflection and privacy. These are variables that have to be taken into consideration.

Finally, I would like to invite MET readers to stop and reflect upon the following questions in light of the daily realities they face in the classroom:

- How do you approach questions in the classroom?

- What setbacks do you encounter?

- How can you make questions a more successful experience for everyone concerned?