Materials evaluation

Materials evaluation is a subjective and belief-driven process of measuring the value of a language learning material for its users (Tomlinson & Masuhara, 2017). This material can be a coursebook, a worksheet or a set of lesson plans.

Teachers and teacher trainers often need to evaluate learning materials, especially coursebooks. Sometimes, the process is as simple as flicking through the pages and following one’s instinct. However, in order to make a more effective evaluation, the process should be principled and more systematic.

Last year I completed the NILE Materials Development module as part of my MA in Professional Development for teachers. I learnt how to develop a criterion-based instrument in order to evaluate and compare two coursebooks before using them, which is called a pre-use materials evaluation.

In this article I will explain this process, step by step.

The context

To begin with, here is a brief description of the context in which the selected coursebook was to be used.

The target group consisted of eight 14-year-old Greek teenage boys at intermediate level. The main course objective was to achieve B1+ level by the end of the academic year. Most of them tend to sit the Cambridge B2 First when they reach that level; therefore, some exam training starts at B1+.

Classes are communicative, with language and skills taught in context. Students struggle with fluency, pronunciation and exam tasks. They seem to enjoy communicative activities and disengage during drills, i.e. controlled activities.

The evaluation process

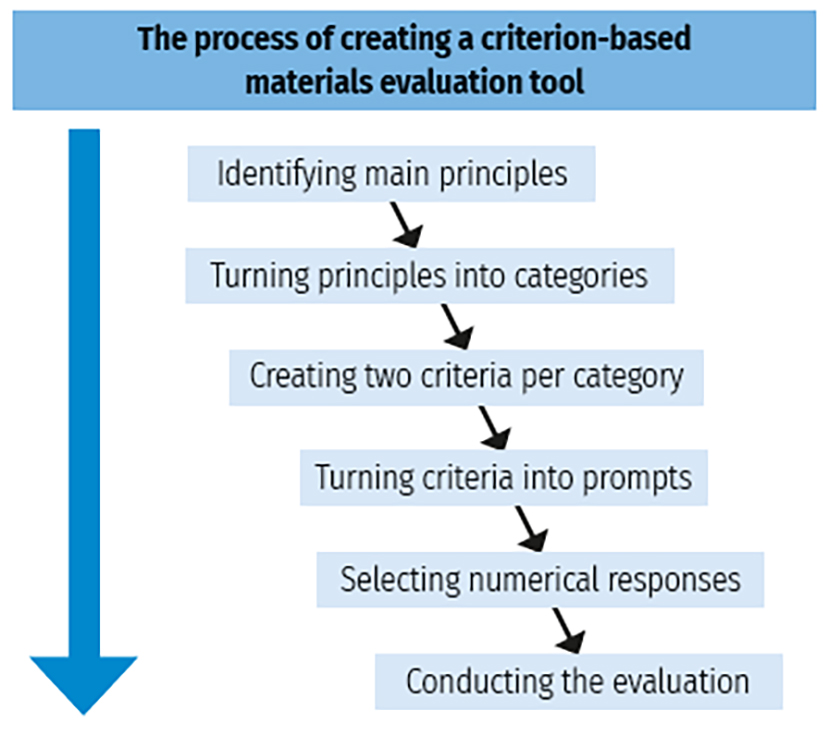

To ensure a principled and systematic evaluation, I developed this criterion-referenced instrument, following the steps in Figure 1.

Step 1: Principles

The starting point of an evaluation should be our principles about second language acquisition (SLA), in relation to the specific learners (e.g. their needs and challenges). This can achieve validity of the criteria and thus the evaluation; the instrument is more likely to collect the responses it is intended to collect, as well as determine whether the materials are teaching what they should be teaching and how they should be teaching it.

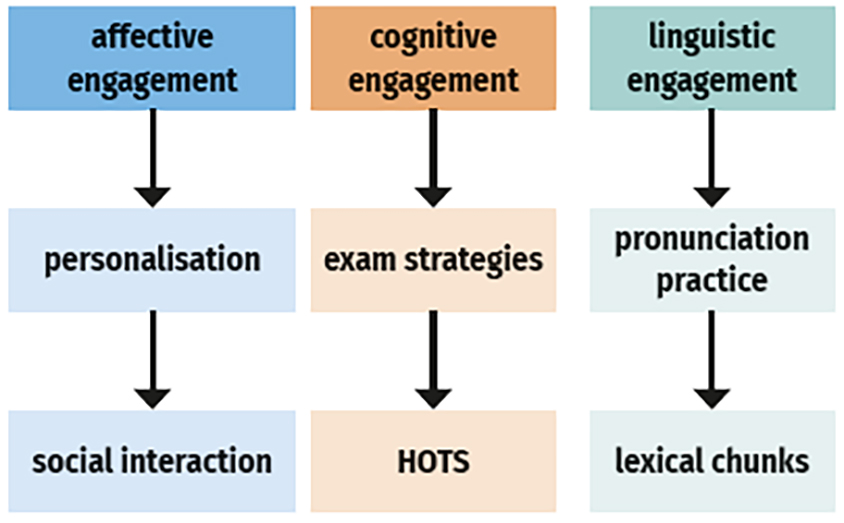

My three main principles for effective SLA, which will be discussed next, can be summed up as: it is crucial for materials to engage learners affectively, cognitively and linguistically.

Affective engagement (AE)

Engaging learners affectively or emotionally may facilitate the cognitive process (Arnold, 1998). As Puchta (2014) explains, chemicals (e.g. adrenaline, dopamine and serotonin) help neuronal networks grow and create bridges between neurons in the brain. Simply put, feelings of pleasure may boost memory and learning, as well as sustain motivation. My teenage learners often experience fluid motivation, perhaps due to mental and physical changes they are undergoing. These changes may impact their language ego – the second identity one develops when learning an additional language (Brown, 2000). Consequently, their vulnerable, defensive ego may hinder SLA. In my experience, affective engagement can be enhanced through personalisation and interaction, as will be argued later.

Cognitive engagement (CE)

Apart from being emotional, human beings are also intellectual (Brown, 2000). SLA requires mental processes such as memorising or storing information in one’s long-term memory, as well as the ability to retrieve it for spontaneous use, which is called ‘automation’ (Sweller et al., 2011). As teenagers develop cognitively, they increase their attention span and ability to work more independently and think critically. These processes can be enhanced through strategy training and use of higher order thinking skills (HOTS).

Linguistic engagement (LE)

SLA involves mastery of vocabulary and grammar, as well as pronunciation – both segmentals, (vowels and consonants) and suprasegmentals (stress and intonation) (Roach, 2000). These exam learners need to focus on both accuracy (i.e. correctness) as well as fluency (i.e. conveying meaning without worrying about mistakes).

Step 2: Identifying two criteria per category

After identifying principles, or categories, six equally important criteria were created, two per category. The criteria show the priorities for this specific group of learners, based also on my main principles about SLA.

Personalisation

Personalisation refers to linking language to one’s life (Senior, 2011) which can be highly motivating according to Hedge (2000). Teenagers are often associated with egocentricity or as Lewis (2015:10) puts it ‘they are the centre of their attention’. Therefore, it could be argued that talking or writing about themselves could increase their AE.

Social interaction

Adolescence is associated with inhibitions about self-identity and a fragile ego, which may lead to introversion. This introversion could hinder SLA according to Brown (1999), whereas extraversion can make a positive impact. How can we enable this? Through social interaction, for example, pairwork, groupwork and cross-classroom interaction.

Exam strategies

Learning strategies are operations students can employ to regulate their learning and become independent. These operations promote agency (Oxford, 1990), which appeals to teenagers as they have ‘one foot in the adult world and one in the world of their childhood’ (Lewis, 2015:7). As mentioned earlier, these learners have not yet developed strategies for the Cambridge First exam, which they may sit at some point. Thus, the right book should engage them cognitively by introducing exam strategies.

HOTS

Bloom’s taxonomy is widely used in education for setting objectives and designing assessment. It divides cognitive processes into two categories (Anderson & Krathwhol, 2001:63):

- Lower order thinking skills (LOTS): remembering, understanding and applying

- Higher order thinking skills (HOTS): analysing, evaluating and creating.

The target learners are 14 years old, thus at the formal operational stage of cognitive development (Piaget cited in Brown, 1999). At this stage, between 11 and 16, they become capable of ‘abstraction’: thinking beyond direct and concrete experiences. Therefore, the selected materials should engage learners cognitively by practising HOTS.

Pronunciation practice

Being Greek, I am aware of my learners’ struggles with both receptive (recognising spoken forms of utterances) and productive (producing utterances intelligibly) pronunciation. Based on observation, both segmentals and suprasegmentals can be challenging, therefore the materials should focus on individual sounds, as well as stress and intonation.

Focus on lexical chunks

English language courses in Greece tend to favour grammar or single-word teaching, which explains most Greek learners’ fluency struggles. Their lack of fluency could also be attributed to low ‘chunk’ awareness. Items that can be defined as chunks are verb-noun collocations (do research); idioms (get it off your chest) or gambits (if you ask me) (Lewis, 1997). Raising awareness of these chunks can increase learners’ fluency. Instead of storing and recalling single words, teenagers should focus on word combinations by speaking, writing, reading and listening more fluently.

Step 3: Turning criteria into prompts

After generating six criteria based on my principles and the learner factors, I turned them into prompts, or rather evaluation questions, for example: To what extent does the material XYZ . . .?

These questions explore quality rather than simply elicit a yes/no answer.

Affective engagement questions

- To what extent does the material include opportunities for students to personalise the language?

- To what extent does the material include opportunities for interaction?

Cognitive engagement questions

- To what extent does the material develop HOTS?

- To what extent does the material introduce exam-taking strategies?

Linguistic engagement questions

- To what extent does the material provide pronunciation practice?

- To what extent does the material facilitate learning lexical chunks?

Step 4: Selecting numerical responses

This aforementioned quality will be measured through numerical responses, ranging from zero to three. Zero represents ‘to no extent’, whereas 3 represents ‘to a large extent’. Between 0 and 3 there are no middle or neutral options, which ensures a more nuanced evaluation of the two materials.

Further comments or examples can be listed in a separate column, to add a qualitative element (Tomlinson & Masuhara, 2018).

| Grade 0–3 0: to no extent 1: to little extent 2: to some extent 3: to a large extent |

Comment |

Step 5: Conducting the evaluation

Once the evaluation instrument was created, it was used to compare and evaluate the two coursebooks. The one with the highest score was selected but adaptations were made. No coursebook is ideal; it is a matter of choosing the best possible fit (Saraceni, 2013:58–72).

| Criteria | UB1+ | OSB1+ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 0-3 0: to no extent 1: to little extent 2: to some extent 3: to a large extent |

Comment | Grade 0-3 0: to no extent 1: to little extent 2: to some extent 3: to a large extent |

Comment | |

| Affective engagement | ||||

| 1. To what extent does the material include opponunities for students to personalise the language? | ||||

| 2. To what extent doest the material include opponunities for interaction? | ||||

| Cognitive engagement | ||||

| 3. To what ment does the material develop HOTS (Higher Order Thinking skills)? | ||||

| 4. To what ment does the material introduce exam-taking strategies? | ||||

| Linguistic engagement | ||||

| 5. To what extent does the material provide pronunciation practice? | ||||

| 6. To what extent does the material facilitate learning lexical chunks? | ||||

| subtotal | subtotal |

Conclusion

The insights are numerous and I wouldn’t have gained them without engaging in this fascinating process.

To begin with, materials evaluation is a time-consuming and demanding process; however, it is a useful skill for ELT professionals as they may have to conduct it at some point. The first conclusion I came to was that although a pre-use evaluation is more time efficient, it is simply a prediction that lacks real data (Cunningsworth, 1995). Therefore, its reliability and validity could be increased through the following.

- To ensure higher validity of the criteria, one could conduct needs analyses and generate criteria based on learners’ responses.

- Working with a colleague and creating a joint evaluation tool could result in a less biased instrument, which will synthesise the principles of more than one educator.

- A joint evaluation, i.e. evaluating the materials against the criteria with a colleague, could also minimise bias and provide more reliable results.