There is a significant amount of research that highlights the value of task-based pedagogy like Task-based Language Teaching (TBLT) in creating the conditions in which second language acquisition can occur in as efficacious manner as possible (Long, 2015). Furthermore, task-based approaches emphasise and promote learner autonomy (Baek & Eisenberg, 2021), which is something I personally find essential within the language classroom.

Because of the value of tasks within language education, I wanted to see how I could bring them into my classes, but it was here that I encountered a number of issues. First, the amount of time it took me to come up with a task from scratch. And secondly, while coursebooks go against TBLT, in my teaching context, coursebooks need to be used in some way; in essence, not using the coursebook usually results in complaints from parents or management. So, what’s the solution? Well, for me it was working with what I already had – that is, exploiting the coursebook using a number of ‘task types’. In this article, we will explore how teachers can taskify their coursebooks using three of these tasks, as well as some considerations for when to do so.

Why?

Taskifying the coursebook is important for different reasons: first, the motivational factor. I’ve come to the realisation while observing my own lessons that for many learners the coursebook itself brings thoughts of boredom and ‘schoolwork’. Why? It’s not because working with the coursebook is unbearable, but because this generally means individual, written language work. Using tasks, on the other hand, generally means that learners are communicating with their classmates through various mediums with task completion in mind, rather than focusing on individual aspects of language, and I’ve noticed a much higher level of engagement as a result.

Second, tasks, and TBLT, comply with students’ needs when it comes to effectively developing their communicative skills. That is, the coursebook usually puts form before meaning, because it operates under a synthetic syllabus, which assumes that knowledge about the L2 will lead to learners successfully communicating in the L2 (Jordan, 2021). However, prescribing language forms, and providing feedback on their use, doesn’t align with what we know about second language acquisition. Research (Willis, 2021) has shown that classes that follow a ‘Presentation, Practice, Production’ paradigm are less efficacious at helping learners acquire a language than task-based approaches.

While the intention is neither to undermine the coursebook nor to eliminate its use from our lessons, it is important to find a balance where students can work on the contents from the coursebook but are engaged while doing so. In my experience, this can be managed by taskifying the coursebook. In order to taskify the coursebook, we need to create tasks – but what is a task?

A ‘task’

The concept of ‘task’ in task-based learning has been defined by linguists in many different terms. Long (1985) defined tasks as things that people do in everyday life (e.g. a puzzle), while Willis (1996) defined a task as a goal-oriented activity that leads to an outcome or result. However, the definition I am particularly drawn to is that which is provided by Ellis et al. (2020), who identify four criteria for identifying if a classroom activity is a task:

- There is a primary focus on meaning.

- There is some kind of ‘gap’ that encourages an exchange of information or opinions.

- Learners rely on their own linguistic or nonlinguistic resources to complete the task.

- Learners are primarily engaged in achieving the outcome of the task.

Taskifying the coursebook: examples

Let’s take a look at three examples on how to taskify the coursebook using some well-known task types: jigsaw reading, text reconstruction and matching.

Jigsaw reading and decision-making

A jigsaw reading is where a text into broken up into small texts (Text A, B, C etc.). Learners are also broken into groups (A, B, C etc.) and are given their corresponding text, which they must individually read and then discuss their understanding of the text in their group. Next, one learner from each of the groups joins to form what can be called a ‘mixed’ group, as there will be an A, B and C (etc.) learner in this group. Learners in this mixed group then share the information they have learnt from their texts (without showing each other!), and then must use this information to complete some kind of task.

Let’s look at an example on how this task would go with a specific text. This text (Figure 1) is inspired by a text in the coursebook I was using, but created with the help of ChatGPT.

Peculiar homesA) House on the cliff: The Smith family’s home sits on the edge of a tall cliff, giving them amazing views of the ocean. The house has big windows that make it feel like they are floating above the water. They can always hear the sound of the waves crashing below. This makes their home peaceful and exciting. They often watch the sunset and enjoy the fresh sea breeze from their balcony. |

| B) Cabin in the woods: Deep in the forest, the Johnsons live in a small log cabin made of wood. Tall trees surround their home, and they can always hear birds singing and animals moving around. Inside, the cabin is cosy and warm, especially with the big fireplace in the living room. They have comfortable furniture and lots of blankets. The family often sits together by the fire, telling stories and enjoying the quiet of the forest. C) Treehouse in the jungle: High in the trees of a tropical jungle, the Gonzalez family lives in a big treehouse. Their home is connected by rope bridges, making it feel like an adventure every day. The treehouse has several rooms, all built high above the ground. The family hears exotic birds and rustling leaves all the time. They love their unique home and enjoy climbing the trees and exploring the jungle around them. |

In this case, the class would be divided into three groups (A, B and C) and these groups would read and discuss their texts. With these particular texts, I extended this stage by having learners draw the house that the text was describing – which is a classic read-and-draw task (another great task to use with learners!). Next, learners would form mixed groups and, without looking at their texts, share the information they have ‘learnt’ about their text (or in this case, the characteristics of their house). Finally, in these mixed groups, students would work together and use all the information they have gathered to match people who are looking for homes to the houses from the texts. For example, the text in Figure 2 describes what Alex likes – I wonder if you can match his preferences to one of the houses described previously?

| Alex: Alex enjoys peaceful environments and breathtaking views. He loves spending time near water, feeling the breeze and listening to the natural sounds around him. Large windows and outdoor spaces are important to him, as he enjoys watching sunsets and being surrounded by serene, natural beauty. A home that feels open and connected to nature would be perfect for Alex. |

Text reconstruction

Another way in which a text from a coursebook can be exploited is by having learners produce something out of the text. For example, the text in Figure 3 (created by Chat GPT, although it resembles a text I saw in a coursebook I was using recently) is a story that learners are supposed to read and then answer comprehension questions about.

| My partner and I decided to have a fun day out at the local aquarium. We were excited to watch the dolphin show. The atmosphere was amazing as the show began, and one lucky grandma from the audience was invited to interact with the dolphins. As we watched with smiles on our faces, the mood quickly changed when, unexpectedly, one of the dolphins bit the grandma’s hand. You could hear some gasps through the crowd and the show had to be stopped. |

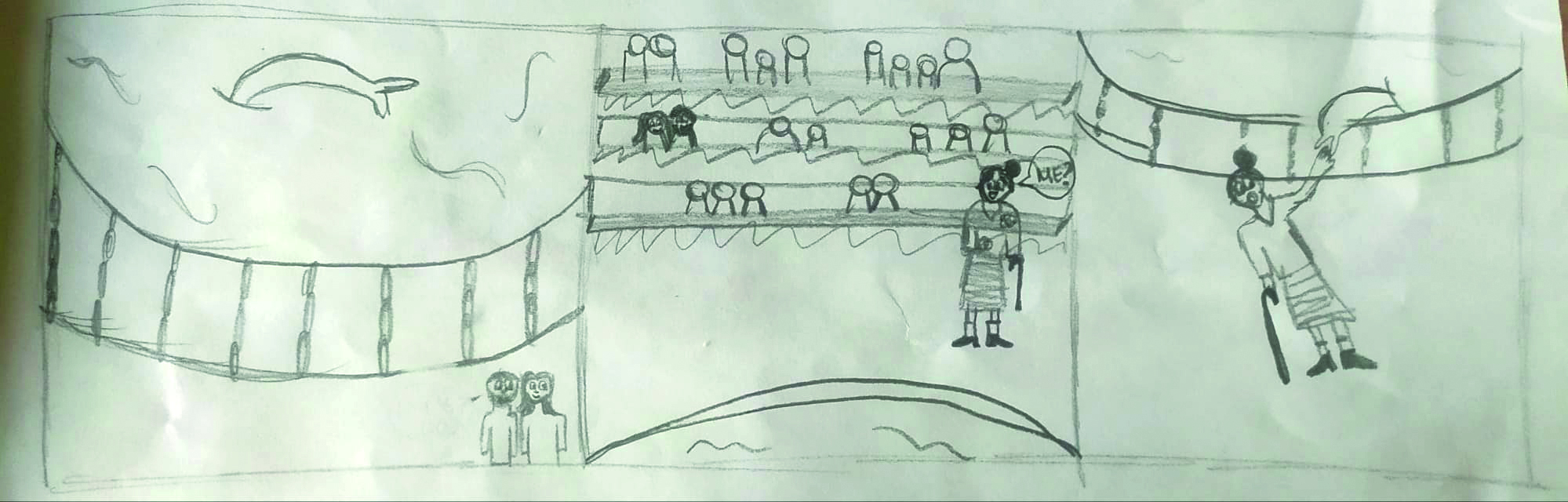

However, what if we have learners read the story in pairs, and then draw the story? This is exactly what I had my learners do. Pair A drew the image shown in Figure 4.

At this level (B1), the classic read-and-draw task is not pushing learners enough, and so we need to include a text reconstruction element. Here is when we can have learners swap their drawings (ideally, all pairs would have had different texts), and then have pairs look at the learner-generated images and reconstruct the story in written format. Figure 5 shows what Pair B produced after looking at the image in Figure 4.

| One day, a family goes into a zoo and they go see a dolphin, someone has to give the food to the dolphin so the public decides. A random woman was chosen. She went next to the dolphin and gave the food. The dolphin ate but he wanted more, and he almost ate the poor human. |

While the produced story is different from the original, it was still a successful task; students in Pair A were able to summarise the story, including the most relevant information, and students in Pair B were able to reflect that in their story. As feedback was provided after the task, and before repeating the process (e.g. ‘to feed’ instead of ‘give the food’; include more details in the story apart from what they can see in the pictures), students were more successful the second time, especially in terms of writing a good story.

Draw my picture

When we talk about exploiting the coursebook, we often look at texts without really considering pictures too. But we can taskify these as well! Exploiting images can be really helpful for introducing a coursebook unit and generating interest about it or even checking how familiar learners already are with a certain topic before getting into it right away. One way to do so is with the task type ‘draw my picture’, where learners have a picture in their coursebook that they then have to describe while their partner draws it. Here they have to talk together, clarify each other’s understanding and work out exactly what it is they need to say or draw (i.e. negotiate meaning). Later, after completing the task, when learners work directly with the coursebook, they can check how successful they were in describing and drawing the picture by comparing their pictures with the ones in the coursebook.

Using tasks with learners: considerations

Before taskifying their coursebooks, teachers should first keep a few things in mind:

- Task implementation is as important as task design. It’s one thing to plan a brilliant task, and it’s another to implement the task. Teachers need to be flexible enough to be able to respond to how learners interact with their tasks, and how these tasks may change during the lesson. In essence, what we plan to occur may not always occur!

- AI is a tool. When it comes to task design, AI turns out to be very useful to complement the coursebook, for example, to create similar texts as the ones we find in it. And we should not feel afraid to use it.

- Allow interaction to occur. During their interaction, students become aware of the gap between what they are saying and what they want to say, and what language they need to close that gap. In these moments, it is important that teachers allow the learners to collaborate and correct each other, without invading.

- Corrective feedback is essential. However, it is still the teacher’s role to drive learners’ attention to form, when necessary, and provide corrective feedback or upgrade their language both during the task and in the post-task stage.