Many of the students I have taught over the years disliked literature with a passion. They often found poetry and prose difficult to comprehend, unrelatable to contemporary contexts, long and old fashioned. However, social media culture, along with the rise of slam poetry in the 1990s and 2000s, has significantly influenced literature trends among young adults. I have often heard students admit they lack the patience to read an entire book but enjoy reading short poems on social media platforms because, despite their brevity, the meaning remains impactful.

This shift led me to rethink my teaching approach. I teach induction classes to young adult migrant learners from diverse backgrounds, ranging from pre-A1 to A2 levels, and I recognised poetry as a good opportunity to help them develop their language skills in a fun and creative manner. While I still believe in the relevance of classic literature, I decided to start incorporating literature into the classroom in a more accessible way, and in forms that students appreciate. This article explores how incorporating multilingual poetry in the classroom can enhance language learning by fostering creativity and inclusivity, as well as enabling students to assume agency in their learning process.

Poetry as a pedagogical tool

My first choice was the haiku. Why? It is a short poem of three verses with a straightforward 5-7-5 syllable pattern, it doesn’t require rhyme, and it usually conveys a deep emotion or insight, making it a powerful form of expression. Born in Japan to capture fleeting moments in nature, haikus have gained worldwide popularity and are now commonly used to describe human experiences as well. Their simplicity in nature and potential to convey a strong message make haikus a perfect tool for teaching English in multicultural classrooms because no matter the quality of each haiku, learners always have a story to share. Poetry writing can be a valuable literacy practice for learners to develop their unique writing voice and increase their linguistic awareness throughout the learning process (Iida, 2017).

First, I introduced students to various haikus covering different themes, paying particular attention to the 5-7-5 syllable pattern. For beginner-level students, counting the syllables of different haikus also helped in the development of literacy skills and phonological awareness. After explaining the haiku structure, we examined a haiku that President Barack Obama gave as a toast during a White House dinner with former Japanese prime minister Abe on 28 April 2015 (McMurray, 2024):

Spring green in friendship

United States and Japan

Nagoyaka ni

Together, we discussed the haiku’s context and meaning. A lot was said about Obama’s choice of ‘Nagoyaka ni’ meaning ‘peacefully; harmoniously’. In which language is it? What does it mean? What does the sound of the phrase convey? Why did the American president choose to use this language in his haiku? What does it show about the relationship between America and Japan?

Exploring multilingual poetry

This exploration of different languages in creative writing, although still not very popular, is on the rise. Antoine Cassar, a multilingual poet from Malta, calls it ‘breathing between languages’. His collection of sonnets ‘Mużajk’ (2008), written in a mix of languages including but not limited to Maltese, English, Basque, French, Italian and German, can be used as an example with higher-level students. Another example of multilingual poetry, also referred to as polyglot poetry, is the famous poem ‘Freeway 280’, written by Lorna Dee Cervantes (1981) mostly in English but including phrases in Spanish. The online Australian Multilingual Writing Project also aims to showcase the linguistic complexities that exist in Australia by publishing multilingual pieces of writing that ‘seek to interrupt, enhance, challenge and generally complicate, the flow of English’ (Australian Multilingual Writing Project, 2018).

However, I wanted to ensure that all students, regardless of their proficiency level, could engage meaningfully with the haikus. Finding multilingual haikus that were suitable for the students’ level while incorporating their first languages proved to be challenging. Therefore, I decided to create my own multilingual haikus to use as exemplary texts in class, and when I ran out of ideas, I used ChatGPT to generate similar haikus in other languages. For instance, here is a haiku I created:

City lights twinkle,

Città, metro, Napoli

Missing you daily.

ChatGPT generated something of a similar structure but a different theme, in English and French:

Sunshine on my face,

Soleil brille, so warm and bright,

A new day’s embrace.

Another possibility for a future lesson would have been for students to critically evaluate AI-generated content and compare it with haikus created by individuals. However, this was not the focus of this lesson, as generative AI was merely used to facilitate lesson planning. Therefore, students explored these haikus, among others, in groups, addressing the following questions:

- What is the general meaning of each haiku?

- Which languages are used?

- Can you guess the meaning of the words that are not in English?

- What feelings does each haiku convey?

Getting creative with haikus

Then it was time for the learners to create their own poem in groups. They were allowed to use any language they wanted, provided that English was one of the chosen languages and that the haiku’s meaning was successfully communicated to the rest of the class. To spark creativity and help them identify a theme, I included some pictures related to the students’ backgrounds and interests. Once the haikus were created, we pinned the poems to our classroom door, which transformed it into a poetry exhibition. All haikus were anonymised and numbered, then students took their time to read them all and vote for their favourites.

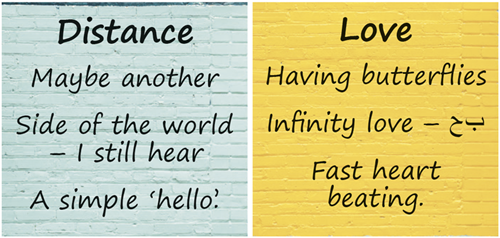

The winning haikus were two. ‘Distance’ was written entirely in English by three male students from Ukraine, Russia and Poland. The other winning haiku, ‘Love’, was written by two female students from Egypt and Albania, and it included the word ‘love’ in Arabic.

These haikus were then painted on the school corridor wall, along with information about the poetic genre of the haiku. This action-oriented learning approach not only allowed learners to showcase their work, but it also increased their sense of school belonging and agency as learners. They will surely remember what a haiku is now!

Conclusion

I found that multilingual haikus worked wonders in my multicultural classroom. Incorporating multilingual approaches enhanced language learning, especially for low-level students. Acknowledging learners’ linguistic identities served as motivation, it lowered the affective filter, boosted their confidence and ensured everyone was participating. Moreover, students found it relevant because it mirrored our daily multilingual realities, as we all interact with people from diverse linguistic backgrounds on a day-to-day basis. Here is a summary of my lesson on multilingual haikus.

- Introduce the genre of the haiku.

- Explore multilingual haikus.

- Create original haikus.

- Vote for the best haiku.

- Transform it into visual artwork.

By celebrating and utilising students’ linguistic diversity, teachers can create a more inclusive and effective learning environment. Combining this with the power of literature and action-oriented lessons makes language learning both enjoyable and meaningful, allowing English to become more personal for students. As Iida (2017) rightly puts it:

Voicing in haiku:

Key to think, see, discover

The meaning of life.