There can be very few English teachers who have never encountered minimal pairs. They are pairs of words like ship and sheep, which are identical except for one sound – in this instance, the vowel. They have long been standard fare in pronunciation materials because they neatly demonstrate meaningful differences in the target language. In fact, minimal pairs have even been used as the title of published books, such as Ship or Sheep? (Baker, 1977). But are minimal pairs really of value in pronunciation teaching – or are they a waste of time? Let’s take a look at some arguments for and against.

Good reasons to use minimal pairs

I would like to begin by outlining three reasons why I think minimal pairs are effective in pronunciation teaching. Later, we will consider some of the arguments against them.

1 Comparing like with like

Minimal pairs allow us to compare like with like. For instance, if you want to demonstrate that there is a difference between /r/ and /l/, correct and collect are very effective examples because they show both sounds in the same context. Two random words containing those sounds such as very and long would be less effective because there are other differences between them apart from the one we wish to focus on, and these might distract learners.

2 Linking pronunciation with meaning

Minimal pairs demonstrate to the learner the link between pronunciation and meaning. If a phoneme distinction does not exist in the learner’s first language, it is easy for them to think it makes no difference. So what if I say velly instead of very – it sounds the same to me! A minimal pair like correct-collect shows that it does make a difference – it can change the meaning of the word.

3 Good for task design

The third reason is of a more practical nature in terms of classroom activities. Minimal pairs can be used in tasks which require the learner to pay close attention to pronunciation. For example, give learners the sentence:

The teacher [a) corrected / b) collected] our homework.

Now say the sentence with either corrected or collected and ask learners if they heard a) or b). Then ask learners to do the same in pairs, taking turns to listen and speak. This small task obliges the learner to pay close attention to the difference between /r/ and /l/. As a task, this is so much more powerful than simply asking them to listen and repeat after you.

Arguments against using minimal pairs

Not everybody is convinced as to the value of minimal pair work in the classroom, and I will outline some possible objections below. I will also explain why I still value minimal pairs, despite these objections.

1 Who needs them?

I’ve often heard teachers objecting that minimal pair work is unnecessary because the context makes the meaning clear anyway. For example, if you hear the words lion cup, you can probably guess the speaker means lion cub, because the context is obviously lions, not drinking vessels. I think the problem with this objection is that it replaces actual pronunciation improvement with a coping strategy. Yes, of course, in real life we will use context when necessary, to help us guess meaning. However, when we come to class, we want to improve, not just learn tricks to sidestep difficulties. What’s more, the context is not always as clear for learners as it is for ourselves. As a simple illustration, take the lion cup example; the learner might not be 100% confident that they heard lion – perhaps it was lying or lime. If they have doubts about the first word, it is less helpful in helping them guess the second.

2 They aren’t authentic

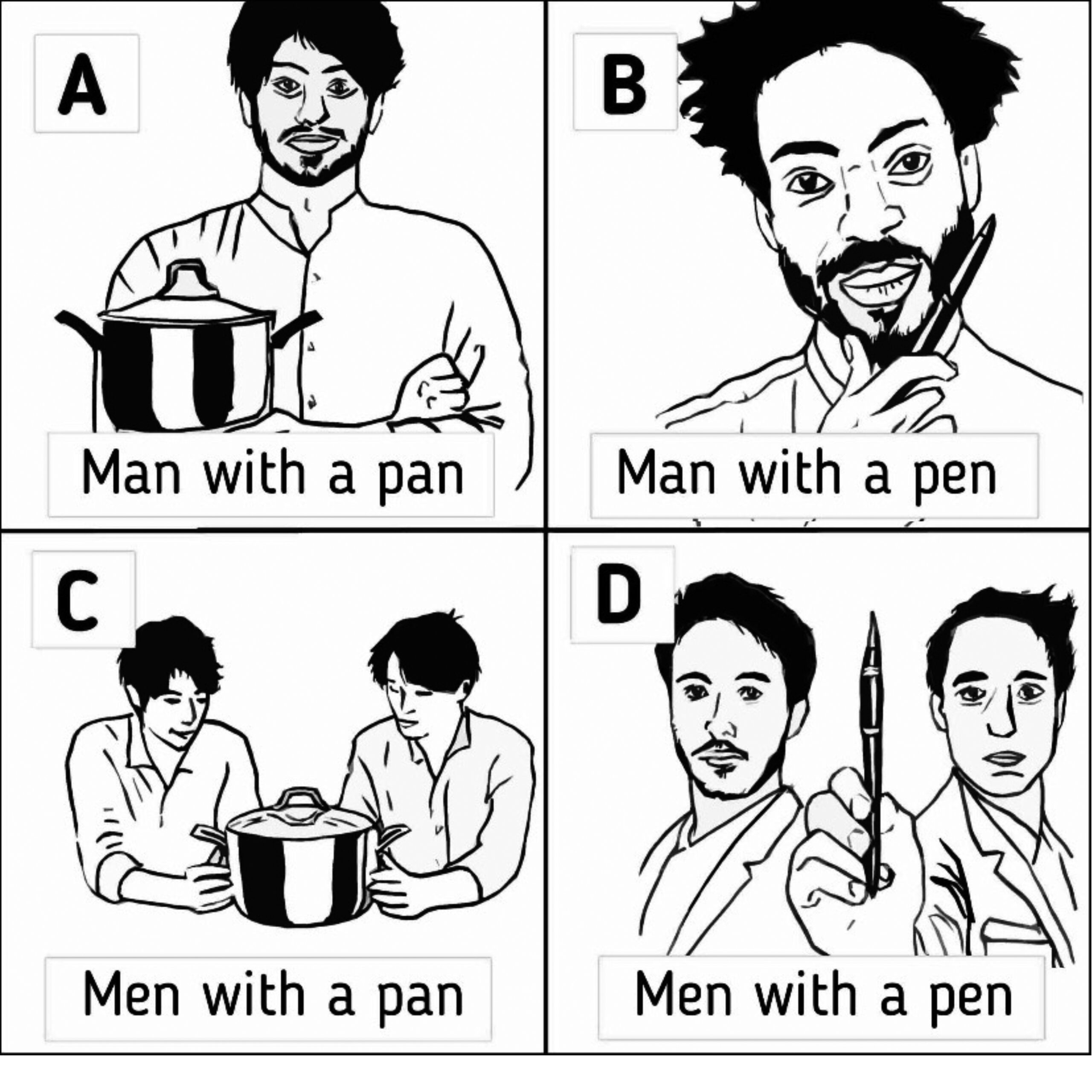

It is perhaps inevitable in minimal pair work that you end up with some rather strange scenarios. Take the material in Figure 1. This is a kind of minimal pair on steroids, combining two minimal pairs: man-men and pan-pen. Inevitably, in order to create meaningful phrases representing all four possible combinations, the scenarios become a bit surreal. I can understand a teacher asking, ‘Would a learner ever need to say that?’ and the answer is ‘probably not’. Nevertheless, the juxtaposition is fun and it is a memorable image – all the more so because of its strangeness, in fact, and it clearly demonstrates the effect of failing to distinguish these vowel sounds in English.

3 They aren’t relevant for everyone in the class

Another objection to using minimal pairs is the problem of relevance for everyone in class. One learner may find a particular sound distinction difficult while the next has no problem with it at all. This problem is especially acute in classes with mixed first languages. For example, the difference between best and pest maybe tricky for your Arabic-speaking learners but no problem for your Spanish-speaking ones – but these might instead have problems with best and vest. A possible solution here is to focus on several related minimal pairs, not just single ones. For example, if you present both pairs, (best-pest and best-vest) there is something for Arabic and Spanish learners. It’s also worth remembering that minimal pairs are for listening as well as speaking. Although a learner may not confuse a specific pair of sounds in their own speech, they may find themselves speaking to somebody who does. It’s useful for them to be aware of this. So, for example, it will benefit the Spanish-speaking learner to know that some speakers of English do not clearly distinguish /b/ and /p/, even if they have no problem with that distinction themselves.

4 Accent issues

Accent issues play a part in discouraging some teachers from dealing with minimal pairs in class. If the material focuses on a minimal pair which does not exist in your own accent, it’s not surprising if you want to reject it. For example, an activity might focus on the distinction between the vowel sounds in grass and gas (these are different in RP) – a distinction which is absent in many teachers’ accents. Such teachers are likely to feel alienated by such material, thinking, ‘I don’t distinguish between the vowel in these words, so why do my students need to distinguish them?’.

This is a valid objection and I would make two points here. First, materials writers should take account of accent variation in preparing pronunciation materials and try to avoid accent bias. Second, English teachers should not reject all minimal pairs just because some of them contain accent bias. In PronPack: The minimal pair collection (Hancock, 2024), I distinguish between plain minimal pairs such as correct-collect, which are for productive and receptive competence, and ‘accent test pairs’ such as cot-caught, which are for receptive competence only (cot and caught are homophones for many American English speakers). This responds to the common-sense idea that learners should not be obliged to produce distinctions that many L1 speakers of English do not make.

Conclusion

From what I have said, it will be clear to readers where I stand on the value of minimal pairs in pronunciation teaching. I am very much in favour of them. So now it’s over to you. If you have tired of using minimal pairs in your classes, I do hope I have given you some reasons to revisit them.